For the final assignment of the course, I decided to investigate one of London’s rapidly changing council estates. I photographed a variety of areas, including estates in Poplar, Ladbroke Grove and Elephant and Castle. My inclination to shoot on these estates – particularly those built in the brutalist/modernist style common during the 1960s – stems from an interest in the historical and social context within which they were constructed, and also from the fact that many (if not all) are on the verge of significant regeneration or demolition. With today’s housing crisis in London and the reluctance of local authorities and the national government to take action against the vast property investment that continues to make home ownership and renting unaffordable, examining the history and ideas behind these huge mid twentieth century estates is, in my view, taking on greater and greater relevance.

Photographing these estates can at times be a sad experience, particularly those that show signs of significant neglect, vandalism and petty crime. However the ideas behind their design were certainly benign – clean, modern and affordable housing for people living in the overcrowded slums of inner London. At some point however, the urban planners appeared to forget they were designing housing for people, and soon many of these estates (despite their acclaimed architectural design) became synonymous with dystopian visions of urban collapse, alienation and crime. What went wrong and what caused this reputation? Was it the design of these estates that doomed many of them?

Initially I considered attempting to knit together images from a variety of estates, however with a 8-12 image brief in mind I decided to focus on one estate. I selected the Thamesmead area in southeast London for a number of reasons. Firstly it forms one of the most extensive estates in the Greater London area, and is therefore one of the best examples of 1960s modernist architecture. Secondly, it is somewhat different in it’s use of water (lakes and canals) and other landscape features. The Greater London Council architect Robert Rigg was inspired by housing complexes in Sweden that believed in the idea that lakes and canals reduced vandalism and crime, particularly among younger residents. Thirdly the area is known for it’s use of elevated walkways and raised ‘streets’ so that most of the residences on the estate occupy the first floor and above. The reason for this was the flooding of the area during the 1953 North Sea flood, and so resulted in quite a uniform design feature.

I researched the area and photographed a number of locations, and was immediately struck by how the design of the structure, particularly the elevated walkways and facades impacted the public space on the estate. I therefore formulated a ‘client’ brief based on this research:

A local borough council are seeking the services of a photographer to investigate the impact of architectural design on the public space in a council estate. They are currently assessing the 1960s designed council housing in Thamesmead, hoping to take this evaluation into account when the local councillors meet to propose a regeneration plan for the area. The councillors are particularly interested in the photographer finding evidence of both positive and negative design characteristics, and to show the impact of these on public space. Whilst the expectation is that the focus of the brief will be on the local architecture and urban space, the photographer may produce other findings deemed relevant for the councillors to consider when formulating a future proposal for the Thamesmead area.

Once I had settled on an idea and written the brief, I found it much easier to approach the assignment. As I walked around the Thamesmead area I was able to plan the photos effectively by referring back to the brief. During my research on the estate, I discovered that one of the first complaints by residents after moving in was rain penetration problems inside a number of the residences. Already this proved the inadequacy of concrete for large scale housing, but its flaws became even more pronounced over time. Concrete is prone to moss and lichen growth and cracks easily, and this is something very noticeable upon the estate’s material facade. Another frequent criticism was the dimly lit walkways and inadequate drainage rendering many of the residences inaccessible. In light of this research, I settled on shooting a particular stretch of one of the elevated ‘streets’ on a day of wet weather. I had considered producing a series of black and white images, but I opted for colour images to present a more objective set of images that departed from the standard portrayal of these estates by photographers. As with my previous assignment on Brixton, I chose to use my digital camera to allow for a quicker review and reflection on the images produced. The final 12 images are arranged in order below.

* All images shot on Sony A7 with 28-70mm zoom lens – using variable apertures from F3.5-F8 with ISO set to approx. 400-1600

Overall I feel the final set of images fulfils the brief and actually reveals more than expected by the ‘client’. It highlights poor design characteristics such as using concrete as a building material (evidence of moss growth and cracks in many of the images), flooded and poorly lit walkways, and also reveals how high walls block out views of the outside. The impact of these features on the public space in the images is dramatic. The viewer feels a sense of enclosure, almost as if the estate is a fortress against the outside world, and the absence of plant life or colour upon the facade does little to alleviate the barren concrete and two-tone world of the walkway. The images are effective in creating this impression of being blocked off from nature, as there are hints of trees overlooking the concrete walls and glimpses of the outside world are obstructed by barbed wire. Even upon the walkway there is little that makes the space inviting – the ‘no ball games’ signs, the barbed wire, the concrete walls and the flooded walkway deter rather than encourage the residents to use the space. Even so, there is evidence of a community. The images that show painted walls are a welcome relief from the dark, two-tone walkway. This demonstrates how even a simple splash of colour can alter a space and make it appear more inviting. It is also a sign of the individual and that within the cold, barren atmosphere of the walkway a community can still exist.

There were a number of difficulties encountered whilst I was carrying out the brief. One of the main difficulties was planning for the day of the shoot – once I had found the walkway I wanted to shoot I had to wait for a rainy day, and so waited some time (unexpectedly for England) for a weekend with bad weather forecast. Therefore shooting the assignment was perhaps not done as quick as it would have needed to be in a real life professional scenario. Another difficulty not unanticipated was the length of time it took to travel to the location. Whilst it did not impact me too much, I did realise in a professional context this would be quite impactful on the process.

I also allowed myself a period of reflection before selecting the final shots for submission. Taking the advice of my tutor, I shot mainly landscape oriented shots and I observed this made the final set feel more focused. I also decided to get some of the images printed (see previous blog posts in Assignment Five folder) and stuck them on my wall for a few days. This allowed me to see the images ‘together’ rather than individually on the computer screen, leading me to select shots with a similar style of composition – a decision I felt helped produce a more coherent final 12. I chose to include the shots of the painted wall towards the end of the set to introduce variety and to challenge the viewer’s perception of the location. Whilst the length of time I took for the process was unrealistic for a professional context, I felt I got to practice the stages of a professional assignment. The period of reflection was an especially important part of the process, and a stage I will employ in the future when discerning the final images to submit for an assignment.

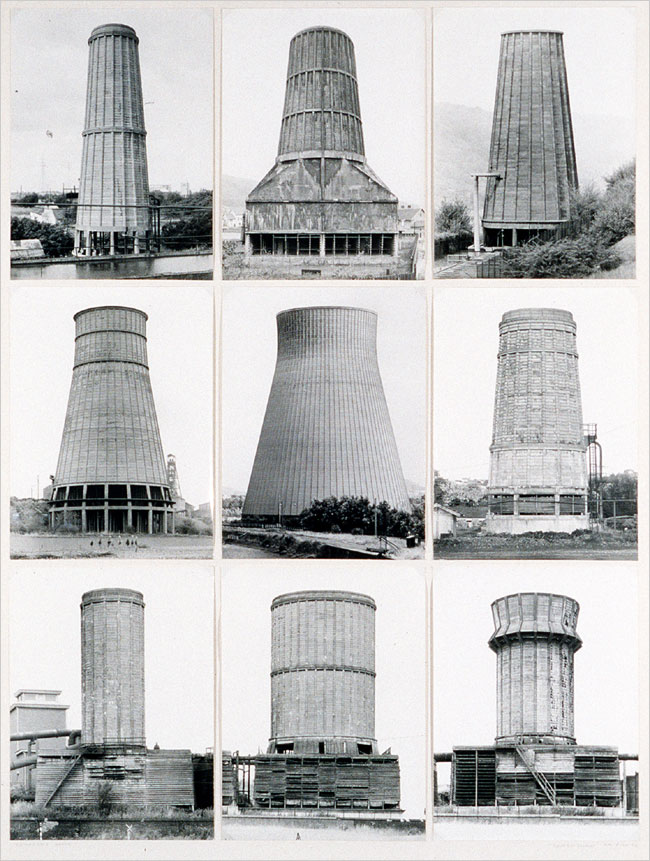

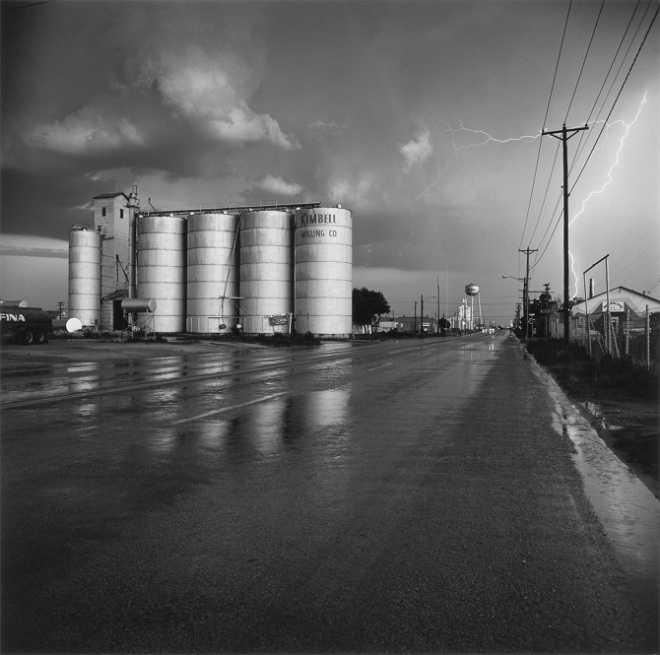

Bernd and Hilla Becher; study of concrete cooling towers; 1972

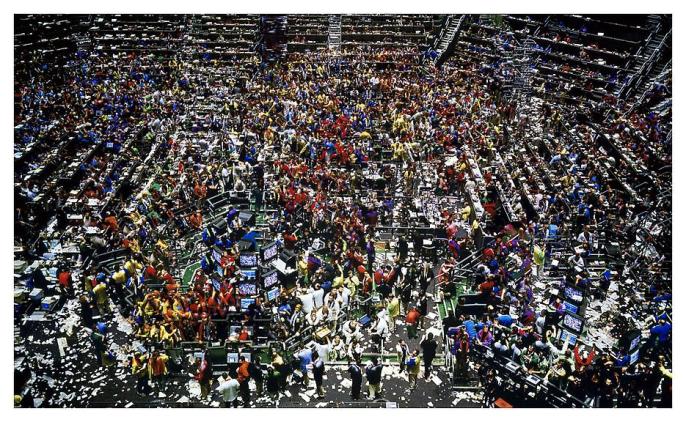

Bernd and Hilla Becher; study of concrete cooling towers; 1972 Andreas Gursky; Chicago, Board of Trade II; 1999

Andreas Gursky; Chicago, Board of Trade II; 1999  Edward Burtynsky; Oil Fields #13, Taft, California; USA 2002 © Edward Burtynsky/Courtesy of Hasted Hunt Kraeutler, New York/Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto

Edward Burtynsky; Oil Fields #13, Taft, California; USA 2002 © Edward Burtynsky/Courtesy of Hasted Hunt Kraeutler, New York/Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto

Lewis Baltz; The New Industrial Parks near Irvine, Element No. 5; California, 1977

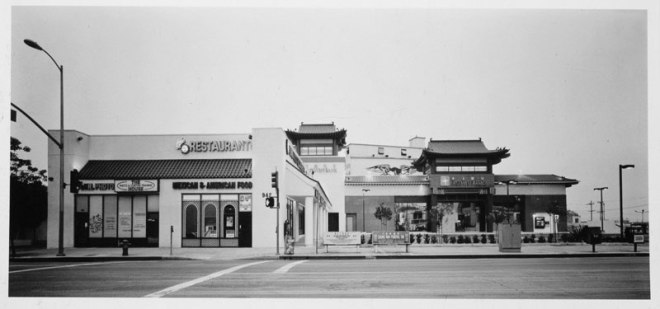

Lewis Baltz; The New Industrial Parks near Irvine, Element No. 5; California, 1977 Catherine Opie; Untitled #2 from ‘Mini Mall’ series; Iris Print, 1997

Catherine Opie; Untitled #2 from ‘Mini Mall’ series; Iris Print, 1997