(P.12-15)

‘The groundwork conducted by artists such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore in teh 1960s and 1970s to establish colour photography over black and white as the main vehicle for contemporary photographic expression is very important.’

‘It was not until the 1970s that art photographers who used vibrant colour – which until then had been the preserve of commercial and vernacular photography – found a modest degree of support, and not until the 1990s that colour became the staple of photographic practice.’

‘William Eggleston began to create colour photographs in the mid 1960s, shifting in the late 1960s to colour transparency film, the kind that is used domestically and commercially for photographing family holidays, advertising and magazine imagery.’

‘The magic of these photographs was their compositional intrigue and sensitive transformation of a slight subject or observation into a compelling visual form.’

‘At that time, Eggleston’s adoption of the colour range of commonplace photography was still considered to be outside the established realms of fine art photography.’

‘But in 1976, a selection of photographers he created between 1969 and 1971 was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the first solo show of a photographer working predominantly in colour.’

‘… the show was an early and timely indicator of the force that Eggleston’s alternative approach would have.’

‘In 2002, the Los Alamos Project was published as a book and as a series of portfolios of dye-transfer colour prints.’

‘The original concept for the project was grand by any standards: two thousand images, taken during road trips between 1966 and 1974 and then printed without captions or commentary in a series of twenty volumes (see Figure 1).’

Figure 1: Lost Alamos, 1966-1974, William Eggleston

‘The Project was inspired by a journey Eggleston had made with his friend the curator Walter Hopps (1932-2005), who had pointed out the gates of the Los Alamos laboratories near Santa Fe, New Mexico, the site where the atomic bomb had been developed …’

‘The timing of the publication of the Los Alamos Project, almost thirty years after it was photographed, reflects the continual growth in the appreciation of art photography’s history.’

‘Stephen shore received critical notice for his photography at a precociously young age.’

‘… in 1971, he co-curated an exhibition of photographic ephemera (such as postcards, family snaps, magazine pages) .. In the same year he photographed the main buildings and sites of public interest in a small town in Texas called Amarillo.’

‘His subtle observations on the town’s generic qualities were made apparent when the photographs were printed as ordinary postcards (see Figure 2 and 3).’

Figure 2: West 9th Avenue, Amarillo, Texas, 1974 (Stephen Shore)

Figure 3: Plains Boulevard, Amarillo, Texas, 1975 (Stephen Shore)

‘Shore did not sell many of the 5,600 cards he had printed; so, instead, he put them in postcard racks in all the places he visited…’

‘His involvement with and interest in pop art, and a fascination with and simulation of photography’s everyday styles and functions, influenced Shore’s coming to colour photography…’

‘In 1972, he exhibited 220 photographs, made with a 35mm Instamatic camera and shown in grids, of day-to-day events and ordinary objects cropped and casually depicted (see Figures 2 and 3)…’

‘Like Eggleston’s The Los Alamos Project, Shore’s early exploration of colour photography as a vehicle for artistic ideas was not commonly known or accessible until relatively recently, when it was published in a book called American Surfaces (1999)…’

(P.16-17)

‘One of the most important influences on contemporary art photographers is the work of the German couple Bernd and Hilla Becher.’

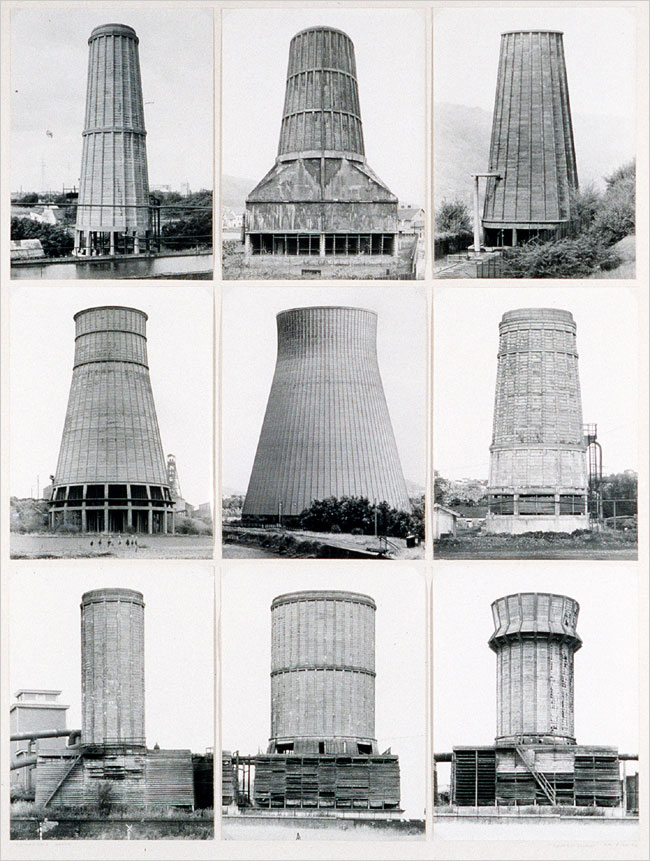

‘Their austere grids of black-and-white photographs of architectural structures such as gas tanks, water towers and blast furnaces (see Figure 2), taken since the late 1950s, may appear to stand in contrast with the sensibilities of Eggleston and Shore, but there is an important connection.’

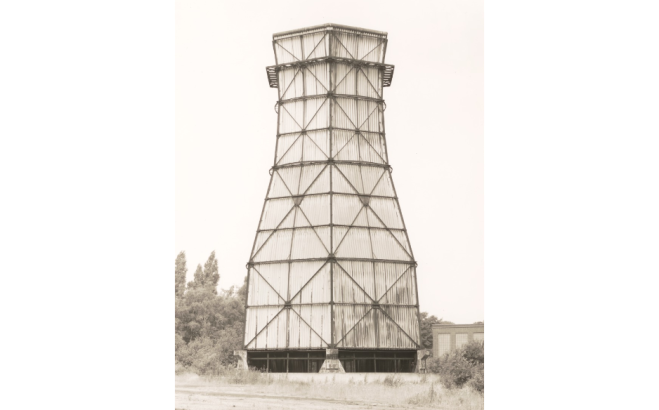

Figure 2: Coolting Tower, Waltrop Mine, Ruhr, Bern and Hilla Becher 1967

‘Like them, the Bechers have been instrumental in rephrasing vernacular photography into highly considered artistic strategies, in part as a way of investing art photography with visual and mental connections to history and the everyday.’

‘Their photographs serve a double function: they are unromantic documents of historic structures, while their unpretentiousness and systematic recording of architecture sits within the use of taxonomies in conceptual art of the 1960s and 1970s.’

‘The Bechers have also played an important role as teachers at the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf. Among their students were such leading practitioners as Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Thomas Demand and Candida Hofer …’

Bernd and Hilla Becher; study of concrete cooling towers; 1972

Bernd and Hilla Becher; study of concrete cooling towers; 1972 Andreas Gursky; Chicago, Board of Trade II; 1999

Andreas Gursky; Chicago, Board of Trade II; 1999  Edward Burtynsky; Oil Fields #13, Taft, California; USA 2002 © Edward Burtynsky/Courtesy of Hasted Hunt Kraeutler, New York/Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto

Edward Burtynsky; Oil Fields #13, Taft, California; USA 2002 © Edward Burtynsky/Courtesy of Hasted Hunt Kraeutler, New York/Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto